English Linen History

Roman Empire Time

FROM PHOENICIANS TO CAESAR

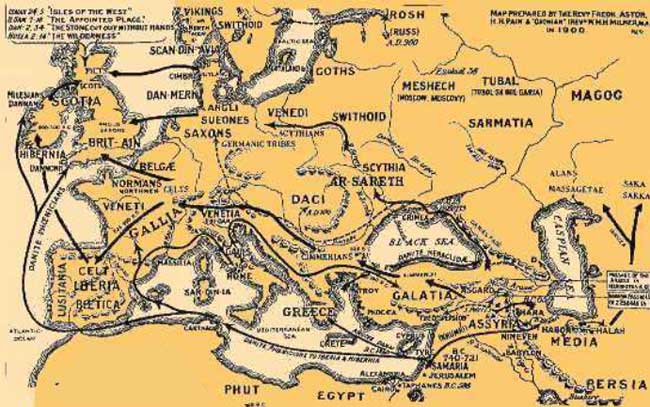

It is well known that the Phoenicians visited England at a very remote period, and for many ages supplied the inhabitants with the productions of Eastern countries, in exchange for tin and other metals from the mines of Cora wall. They were unquestionably the first people who visited Britain for the purposes of trade, as this is positively affirmed by Strabo, and acknowledged by many other authors. After visiting all the coasts of the Mediterranean they passed the Straits of Gibraltar about 1250 B.C., built Cadiz, sailed along the west coasts of Gaul, discovered the Cassiterides or Scilly Isles, and the south-west coast of Britain, Bochart says 904 B.C, but others think only 600 B.C.

This much is certain that Herodotus, who lived 440 B.C, speaks of the Cassiterides as the place from which all the tin came, but declares he does not know where they are. The Linen of Egypt was an important article in the trade of the Phoenicians, and no doubt formed one of the commodities given in barter for the highly prized metals and minerals of England, although Strabo only enumerates salt, earthenware, and brass trinkets, as then British imports. This Linen was much valued by all the nations of antiquity to whom it was known, and doubtless the natives of Britain, although uncivilized, would also prize it. It is fair to suppose, therefore, that Linen may have been first introduced into England by this maritime people, although there is nothing certain known on the subject. After the Phoenician commerce was destroyed, for many ages the rude and barbarous natives of this country had little intercourse with other nations, and the very existence of Linen, if ever known, seems to have been forgotten by many of them.

CLOTHING IN ENGLAND AT THE TIME OF JULIUS CAESAR

Caesar says that the Britons in the interior of the country were clothed with skins. Pliny and others say that the ancient Britons still continued to besmear their bodies with paint long after the people of Spain, Gaul, and even Germany had abandoned that practice and were tolerably clothed. It would appear, however, that some of the people of Britain not only wore various kinds of cloth at the time the Romans first visited the country, but that they were then well acquainted with the art of dressing, spinning, and weaving both Flax and wool, and that they practiced these arts much in the same manner as the people of Gaul Not only was this the case, but they were even the inventors of some particular descriptions of cloth.

One of these was made of fine wool, dyed of different colors, and woven in checks or squares, like the Scottish tartan of the present time. Of this the people made summer mantles and other garments. Pliny says the ancient Gauls and Britons were acquainted with the art of dyeing woolen yarn and cloth. The material chiefly used was the glastum or woad, with which in former times they had dyed their bodies; and deep blue long continued to be the favorite color with which the ancient Britons, and also the Caledonians, dyed their clothes. The dress of the Druids was white, and probably of Linen cloth. Pliny mentions that the priest, arrayed in a surplice or white vesture, climb up into the tree (mistletoe), and with a golden hook or bill cutlet it off, and they beneath receive it in a white soldier's cassock, or coat of arms. Burnt bones have been found in British barrows, secured by a Linen cloth. Some specimens of the Linen were of a reddish-brown color, the filaments at first appearing like hair.

found in a barrow some bits of cloth so well preserved that the size of the threads could be distinguished, and skewed it to be what is now termed a Kersey cloth. The following description of the habit of the great British heroine, Boadicea, is given by Dido and other historians. “She wore a loose robe of changeable colors over a thick plaited kirtle, the tresses of her hair hanging down to her very skirts, with a chain of gold about her neck, and carrying in her hand a short spear or dart." What Tacitus says of the German women may also be true of the Britons" Their dress differed little from that of the men, excepting that the women wore more Linen, but left their arms and part of their bosoms bare." The art of making, and the custom of wearing Linen, were probably brought into England by the Belgian colonies, about a century before the Roman invasion, or perhaps earlier, and at the same time with agriculture, and it kept pace with that most useful of arts in its progress northwards. There is direct evidence that the Belgae manufactured Linen, as well as cultivated their lands on the Continent, and there is thus good reason to conclude that they continued to do the same after they settled in this Island. Although the Belgae, the most civilized of the ancient Britons, were not altogether unacquainted with the most essential branches of the clothing art before they were subdued by the Romans, yet these arts were improved in England by that event.

The Romans learned all the useful and ornamental arts practiced in the different countries throughout their vast empire, and readily taught them to their subjects in other countries where they were unknown, or imperfectly practiced. The Roman invasion of England must therefore have been the means of reviving and extending the use of Linen there, as the Britons were then, or very shortly afterwards, partial to Linen, and used it for many purposes. Pliny describes the different qualities of Flax respectively produced by each country, with a minuteness which shows that the manufacture of Linen was then an important branch of trade among the Romans, and that wherever their arms penetrated Linen would soon be known. It appears from the Notitia Imperii that there was an Imperial college or manufactory of woolen and Linen cloth for the use of the Roman army in Britain established at Venta Belgarum, now Winchester.

Further readings

Textile Manufactures in Early Modern England By Eric Kerridge

© 2015 - Belovedlinens Terms of Use Privacy Policy Contact Us